Gladwelling, Finding Truth in Social Science, and Marjorie Taylor Greene

Like many people, I had a lot of extra time on my hands in the last few months. And also like many, whether I liked it or not, a lot of that time was spent trying to figure out how precisely the US ended up in this desperate place. One pressing question, among so many: have people gone crazy, or were they always this way? I suppose I have a lot to say about this, but here I want to provide my travelogue from my last few months on the topic.

First stop: The Science of Conspiracy Theories

Since even Fox news is talking about conspiracy theories, we begin our retelling of the journey somewhat in the middle by checking in with a survey of scientific conspiracy theory research. The most sobering part of the article is that the only real defense we have against conspiracy theories is a potent and aggressive offense. In fact, it might just be the case that the only way to free people from conspiracy theories is to travel back in time to prevent them from chasing that bunny to begin with. On the other hand, there seems to be some encouraging evidence that at the very least children can be inoculated against misinformation. On another note of optimism, I’ll add that in the New York Times’ extensive coverage of QAnon, most of it deeply depressing, recently there appeared a story about what recovery from QAnon looks like.

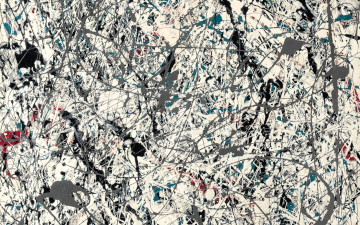

However, going back to the first article, one study in particular caught my eye. In 2017, van Prooijen et al. reported finding correlations between an individual’s tendency to believe in conspiracy theories and their apparent ability or tendency to see structure in random patterns. They presented subjects with randomness in the form of random strings like “HTHHTTTTHH” (representing heads and tails of a coin flip), and “unstructured Modern art paintings.” The idea here is that if you tend to believe in conspiracy theories, then you also tend to believe that there is an hidden pattern in this:

Figure 1: A section of Jackson Pollock’s painting Number 19

Figure 1: A section of Jackson Pollock’s painting Number 19

This study is intriguing and it’s conclusion seems profound, but this brings us to another, previous destination on our journey. In my efforts to understand what befell our society, I’ve read more social science papers in the last six months than in the previous 47 years combined. After a handful I began to get an uneasy feeling. Like many, I am aware of the replication crisis in social sciences, but I didn’t quite understand what was going on until I started reading psychology papers. In particular, while not a paper, I decided to dust off my unread copy of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow. I had resisted reading it for years out of my sheer innate antipathy to following trends. However, with all of this psychology I was reading, I felt my guard dropping and I was ready to give it a try.

Next Stop: How to Not Get Gladwelled

The first chapter wasn’t bad at all. In fact, Kahneman seemed like the kind of scientist who could earn my trust. However, that night, after reading Chapter 1, I awoke in a cold sweat. Was I being Gladwelled? In my parlance, being Gladwelled is a situation wherein you have lent your attention to someone, be it in a book or a TED Talk, in which the auteur involves you in an intoxicatingly neat and novel account of some important topic, revolving around some singular scientific individual or study that seems to explain everything.

Your immediate reaction is of gratitude to the originator of the tale for showing you something so obvious, yet so deep, hidden from you by your own intellectual limitations. And boy does it go down easy. The problem with this state of affairs is that, quite often, if you look at the whole field from which this singular example is taken, you are just as likely to find contradictions as confirmations. This magical result, around which the story has been built, has been simply cherry picked from a large corpus of research, where a legion of researchers, not usually among them the person telling you this story, have spent their entire careers creeping toward a methodical understanding of their complex topic.

I bring this up in regards to Thinking Fast and Slow because Kahneman has acknowledged that in Chapter 4 of his book, he loaded up on cherry-picked studies with low statistical power, and neglected to include studies which failed to support his conclusions. In his own words:

What the blog gets absolutely right is that I placed too much faith in underpowered studies. As pointed out in the blog, and earlier by Andrew Gelman, there is a special irony in my mistake because the first paper that Amos Tversky and I published was about the belief in the “law of small numbers,” which allows researchers to trust the results of underpowered studies with unreasonably small samples. We also cited Overall (1969) for showing “that the prevalence of studies deficient in statistical power is not only wasteful but actually pernicious: it results in a large proportion of invalid rejections of the null hypothesis among published results.” Our article was written in 1969 and published in 1971, but I failed to internalize its message.

For the sake of Internet posterity, Kahneman here is replying to a blog post by Ulrich Schimmack, who on his blog takes researchers to task for publishing studies with low replicability. As Schimmack says in the post to which Kahneman is responding:

Every reported test-statistic can be converted into an estimate of power, called observed power. For a single study, this estimate is useless because it is not very precise. However, for sets of studies, the estimate becomes more precise. If we have 10 studies and the average power is 55%, we would expect approximately 5 to 6 studies with significant results and 4 to 5 studies with non-significant results.

When reading surveys that purport to make a point based on the accumulated “research,” pay special attention to whether the author presents non-significant results along with the cases that the author believes makes his point. Non-significant results can come in different forms, from studies burdened with confounding factors that spoil the outcome, to worse, reporting effects that are too small to be supported by the sample size. One aspect of the replicability crisis, as yet unsolved, is that not only is it difficult to publish non-significant results, but there is fundamentally little incentive for researchers to do so.

Scientific studies that survey the entire field without bias are termed meta-analyses. If your object is to ground yourself in the best evidence out there, pay attention to them. As an example, despite the fact that Angela Duckworth built an empire out of Grit, a 2017 meta-analysis of 88 samples representing 66,807 individuals failed to confirm the “higher-order structure” of the trait. Her TED talks are great though.

Here we connect our first and second destinations on the journey. With either an individual enthralled by a conspiracy theory, or an author cherry-picking studies to make a point, we find ourselves confronted with someone seeing patterns that probably don’t exist. This returns us to the 2017 by van Prooijen et al. study reporting correlations between belief in conspiracy theories and seeing patterns in random events.

There’s another important rule when reading social science, touched on by Kahneman in his quote: when reading any single study, look at the size of the effect. If the effect is small and the sample size is small (a matter of taste – a dozen or less is very small), drop the paper in the trash. On the other hand, if the effect is small and the sample size is reasonable (a hundred or more), then you need to do one of two things: either place the paper aside and wait for more results, or even better, a meta-analysis; or, go replicate the results yourself.

I bring this up for the 2017 study, because for me, the effects are too small. The authors report the intercorrelation coefficient between “Belief in existing conspiracy theories” and “Illusory pattern perception” in a string of H and Ts like “HHHTTTTTHH”, as 0.37. If the phenomena were totally uncorrelated, that value would be zero. If they were perfectly correlated, it would be 1.0. So, while interesting, that effect size is too small for me, despite the fact that they studied 264 participants. It certainly could be true, but I’ll wait for the meta-analysis.

Initially the 2017 study drew my interest because instinctively, I wanted this result to be true. Like I said, I’ve had nothing but time on my hands, and I could ruminate on the implications of this study for hours, if not days. And it’s a great talking point with your liberal friends and relatives, whether you want to say “look at those crazy people seeing a pattern in Pollock (they probably didn’t even think it’s art anyway),” or you want to say “maybe there’s something about human nature – we should engage them.” Either way, the point here is that we should say neither. There is no shortage of ideas out there in the social sciences, so just move to evaluating the next one.

Third Stop: What science is Really About

We now come to the third and penultimate destination on our journey: what science is really about. Returning to the second part of Kahneman’s comment on Schimmack’s blog:

My position when I wrote “Thinking, Fast and Slow” was that if a large body of evidence published in reputable journals supports an initially implausible conclusion, then scientific norms require us to believe that conclusion. Implausibility is not sufficient to justify disbelief, and belief in well-supported scientific conclusions is not optional. This position still seems reasonable to me – it is why I think people should believe in climate change. But the argument only holds when all relevant results are published.

So straight after his mea culpa, he appears to be walking straight into another pile. Proponents of the cultural critique of science will see strong evidence for their claims in Kahneman’s statement. If you followed the controversy around Timinit Gebru and Google, you know that the critique challenges the fundamental basis on which research gets included in the “large body of evidence published in reputable journals.” A balanced view says that the process of publication, no matter which discipline, is always far from meritocratic. As Gebru’s story shows, often it’s not just the editors of the journals who control admission, but the individual researchers themselves.

But even aside from the cultural critique, Kahneman is plainly misunderstanding the purpose and practice of science. Just as it is the professional responsibility of the doctor to cause no harm, the lawyer to advocate for their client, the plumber to make sure the water is safe to drink, the professional obligation of the scientist is to be vigilant to the results of any experiment that informs their field of expertise. And when those results arrive, the scientist is obligated to update his or her beliefs about truth. The point of the literature is not, as Kahneman implies, to establish objective truth in the literature. The point is to provide individual scientists with the credible evidence they need to fulfill their duties to their field and to society.

Kahneman’s quote paints the wrong picture of objective truth in science. The pursuit of scientific knowledge is not about getting your work on some all-time greatest hits list in the history of ideas, or about proving to your doubters that you were right all along, or even about pleasing God. The purpose of scientific knowledge is to inform a scientist in such a way that he or she can take what they believe into their lab and assemble some ingenious contrivance that materially progresses the future of our world. There are an infinitude of ways to pour chemicals into pieces of glass, but only a small handful that produce fertilizers. The recipe is in the literature. You read a paper, mess around in your lab, and next thing you know you’ve invented a new kind of battery. Before long, there are millions of your inventions out in the world, hundreds of which at one point in time were converged upon the US Capitol building, in peoples hands while they took selfies during an insurrection.

Two hundred and fifty years on from the Enlightenment, the general public still doesn’t understand that scientists never know anything with absolute certainty, yet possess the most durable knowledge of our reality available to us. And what eternally confuses people is that despite scientific consensus, there are always results that challenge that consensus, just as we saw that for every argument for meaningful effects in humans, we require that there be a certain number of non-significant results presented. van Prooijen et al. aren’t wrong, it’s just that I don’t believe that the evidence supports the conclusion, yet.

Frankly, if lay people are really paying attention to science, they ought to be accustomed to this. Regrettably, our public discourse has more than its share of charlatans who take advantage of the public’s ignorance by claiming that the slightest sign of contradiction is justification for throwing the whole thing out. But frankly, the participation of these charlatans is still all part of how this sophisticated system of truth works. Science demonstrates to us a system of thought that is remarkably resilient to assault on its principles.

Before I go on, I’ll note that I’m still going to read Thinking Fast and Slow, albeit slowly. I cut Kahneman some slack for two reasons: one, despite the fact that he doubled down after capitulating, he did it, in all places, on a blog. The truly damning response, to him and not Schimmack, would have been to publish his response to the blog as a letter in one of the journals he seems to trust so much. Kahneman clearly values intellectual integrity.

The second, and much bigger reason I cut him slack is that prospect theory, the research for which he was awarded the Nobel prize in Economics, is one of the most replicated results in social science, born out by multiple meta-analyses. So while he may have been reaching a bit in Thinking Fast and Slow on topics like priming and bias, and you should be rightly weary, you also absolutely should study what he and Amos Tversky discovered about the way in which the framing of choices affects the decisions that humans make about risk. In fact, they have a lot to teach us about our present situation in the US.

If you are a scientist, your dedication to your discipline transcends constant vigilance. You really ought to never sleep soundly at all. It is entirely possible that tomorrow morning we could all wake up to an article in Nature that reports a violation of Newton’s First Law, which states that objects in motion tend to stay in motion until they are acted upon by an external force. Now, it is quite a bit less likely that this violation would have been observed in the world that we touch and feel every day. But it’s certainly possible that this scenario could play out in the realm of the exceptionally small, beyond our current theories of the universe.

Because of Newton’s first law, we understand conservation of momentum, and what happens when a car rams a brick wall at high speed. Because of this new result tomorrow, scientists will be forced to update their beliefs about the world. Not only would they do this out of duty, but it would be the single most exciting thing that ever happened in their careers, because it would mean the promise of new, undiscovered knowledge of the universe. But normal lay people would undoubtedly read about all of this in the New York Times, or hear about it on Fox News, and despite the best efforts of the journalists, all of the complexity and constraints on the conditions around the result would fail to be conveyed.

And so, your average citizen would probably ignore the news. But a small but not insignificant portion of the US population would see in it the confirmation that scientists are wrong, and that momentum conservation is fake news. But how many among them would be so certain of their beliefs, so determined to prove themselves right, that they might hop in their car, head out on the highway, and intentionally plow themselves into the median? Despite everything we’ve seen in the last months, teasing more elasticity from our jaws than we ever thought possible, I think we’d all be properly shocked to hear about that happening. People couldn’t possibly be that crazy.

Last Stop Before Crazy

This brings us to the last stop on our tour, aboard the train bound for crazy, where all exit, save a few, such as those who might drive their cars into walls. It used to think that train was empty. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s beliefs are well documented, but apparently the latest revelation of her past statements is too much even for the Republican congressional leadership. I don’t know exactly where she gets her information, nor frankly do I ever wish to find out. But she appears to be so brazen, so detached from reality, that her behavior might be just as self-destructive as running her car into a mass of concrete to prove a point. So, to my original question, whether these people are just crazy, or something else, in the case of Greene, I conclude simply that she’s deranged, and reserve the more subtle frameworks we get from social science for the less self-destructive.

However, for those of us who got off the train, we find that we’ve arrived in a difficult place, since from where we stand we can see that there are many more like Greene than we would have previously imagined. In their brazen self-destructiveness, their willingness to defy the existence of a shared reality, their hatred for science, they resemble suicide bombers intent on destroying not just our democratic institutions, but our rational system of beliefs.

I can’t say that I know what to do about all of this. But time is of the essence, and we must move quickly, but not hurry. What I can say is that the success of science shows us that if we remain patient and open minded in the face of both confirmation and contradiction, refuse to amplify ideas that fail to meet our individual standard of truth, resist the urge to cherry-pick and pile on to the latest explanation, and demonstrate a commitment to the knowledge that grounds our shared reality, then we can tolerate all manner of challenges, and forge together a bond of belief that will yet lead to a productive future.